The Ten-Year Play

When the excitement of creation comes from newness and experimentation, where does the energy come from ten years on?

Ten years ago, in a tea room in Austin, I was hired to teach theatre at this tiny private school next to a paintball place on Fitzhugh. The name has changed, and we moved into our own place deep in Dripping, and over ten years it’s been a ship of Theseus; yet, the school sails with the same innovative energy. Playwrights don’t run theatre departments, we are frequently nomads wandering from whichever city and theatre will have us, so I had no inklings back then that this conversation over tea would become my life’s work.

A story has a thousand beginnings, but I can pinpoint two turning points. The second was when the middle school students elected to do an LGBTQ reimagination of Romeo and Juliet, a department-defining project where the scope required our first after-school rehearsals, and with which we demonstrated the unfortunately radical notion that theatre-with-middle-schoolers can be art because it’s with middle schoolers, not despite it.

“Romeo” visits the apothecary

2016

My first turning point was my first semester’s Production class. I started with five - Fletcher, Ian, Audrey, Asia, and Sam - and we were looking for scripts to produce. I’d found a few texts - a slimmed down Scottish play, a chunk of Wiley and the Hairy Man, a couple other plays floating around the HS/JH ecosystem - and the students read these. A play that fits five (later six) in a mixed JH/HS class is a rare thing, though, and these texts didn’t feel right.

That was when Ian mentioned a dream where he was surrounded by ‘hollow creatures.’ I was struck by this sentence. I turned this sentence into a scene, and brought pages to class the next day.

And as the kids huddled around Sam (who’d later play the nameless lead) and became the hissing, hollow creatures, it was clear that this was the play we needed to create. Our task was to make the one with the script that didn’t exist.

Which is scary.

Even though I’d written plays under commission and with ensemble-based script-building processes, even though this play was barely half an hour, there’s something scary about pinning the success of a new teacher on an empty page.

And yet, success was what we found with Nameless in the Desert.

In ten years, I’ve written twenty-one plays with my students.

Your first play is the easy one. Scary, yes, and challenging because your craft skills are still being refined, but you haven’t established your own clichés to escape. You can do anything because you haven’t done anything.

The twenty-first play is hard.

Theatre is temporary by nature. It’s art in time, and ephemeral by definition. And as a playwright, I’m perpetually restless. I want to make something different every time. I make things because I don’t want to do what other people have done before - let alone what I’ve done before.

So, ten years on, twenty plays later, how do you make it new?

Last fall, my answer was to do an issues-based play -- new to me and the students, but not to the form. What electrified me first was creating a student-driven process to identify the topic. And that’s a much longer story that would require several more thousand words than I’ve allotted myself.

This semester, as I approached my ten year mark, I itched for reinvention.

I knew the play had two starting points. Firstly, one student came up to me and said, “I think it would be cool if the play was in one place.” Secondly, I had an incredible set of theatre tech students I wanted to challenge.

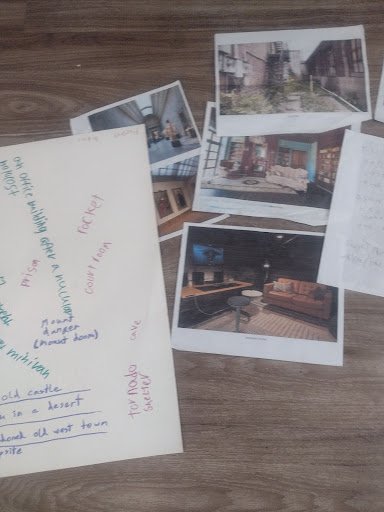

We started the usual (for me) way. Gathering locations, pulling images. From there, the students created tableaux and performed improv inspired by these different locations. Eventually the setting emerged: a cave.

Images and poster dialogues leftover from the process

Now, here’s the thing: we’ve done ‘design-based’ theatre before. This otherwise radical inversion of the play-creation process is not new ground for us. In 2018, we built the middle school play out of a student’s set design, and in 2022, our spring production was thematically connected to a four-person set design class. So, how would this play be different if we were starting from similar ground?

The set designer and others and I visited a cave tour led by a former student.

A “cave painting” from the devising process

Something happened though: the kids kept making the harder choices. Many of these students are natural comedians, and while there are moments of funny in the play, this is not a comedy. They wanted to make the weirder, artsy play, the one unlike any we’ve done before, the one about human connection and loneliness.

Take this example — this could be a play about gold being hidden in a cave. As students improvised scenes, we absolutely had the option of making a series of stories about people discovering the gold and hiding the gold and treacheries as they search for this gold. And that would certainly be an easier play to write. It would be a puzzle to solve, and puzzles are satisfying. And that was an option I kept open for the students.

They didn’t take it. They didn’t want the gimmick, they wanted something stranger, something driven by theme and character, not by plot.

And secretly, I did, too.

Students improvising a scene exploring the cave. Note the ‘hidden treasure’ under the bench.

Because the play about ‘who-has-the-gold’ is not deeply connected to the cave itself. The cave is setting in such a play, whereas the gold becomes the Maltese Falcon the story pins itself to. In our cave, the cave is active - it’s a theatrical conceit itself, a realized metaphor for grief, isolation, guilt, the creative process, and so on.

And the kids got that intuitively. In fact, when something that didn’t work with this metaphor - even scenes I liked - popped up, they’d tell me that it didn’t work.

I didn’t know where I was going writing this play, but I didn’t really need to. I was lost, yes, in this cave, but I wasn’t alone. I was with them, on the same page.

Students devising a scene based on my ‘requests’ and some of the characters in our cave (the characters are on the notecards on the floor).

Perhaps the strangest thing to happen was that we cast the play early, without auditions. We never do this. No one does. When I realized something felt different as each actor had attached themselves to different characters, together we came up with a system where the students would rank which parts they wanted. Any overlap and the actors would specifically audition for that role. Essentially, we’d skip to callbacks.

The dangers were many. I pictured a handful of actors duking it out for one role. I imagined roles no one wanted, hurt feelings on the part of whoever was saddled with them. Dogs and cats living together. Mass hysteria…

Except something odd happened; almost every actor got their first choice. One actor got his second choice, but even that wasn’t contentious.

I can’t recommend others do this. The idea of ten actors casting themselves without conflict is unheard of.

Instead, I regard this as one of the markers of what makes this semester unique.

What this magical moment revealed to me is this is the play for this particular set of young people.

And here is the answer to that question of how do you renew after ten years and twenty-one plays. The ensembles change from play to play as new students enter and our graduates move on. The actors themselves change - a teenager is a different person every month. Our theatre tech students develop new skills and interests. And so each play gets to be a portrait of a moment, lightning bottled, new and different and exciting.